A short history of yoga marketing

I’ve been thinking a lot about visibility lately. About how easy it is to dismiss marketing as something separate from the “real” practice. About how often I’ve heard, even from sincere teachers, that “yoga and promotion shouldn’t mix.” But when I look at the history of yoga, the story is not about silence. It’s a story of voices, stages, microphones, film reels, celebrity faces, and now, screens. It’s the story of how yoga travels. This is not a story about algorithms. It’s about how we tell the story of yoga, and who gets to tell it.

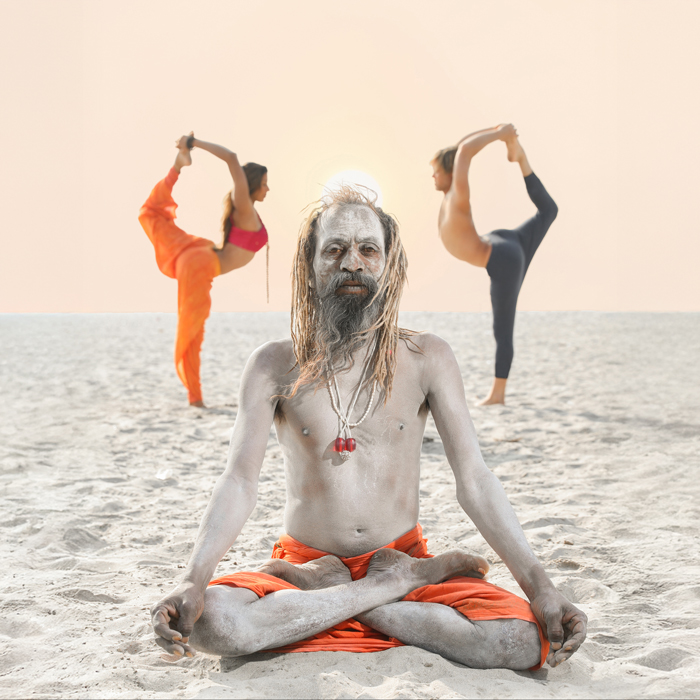

Patanjali and the vision of renunciation

The roots of yoga are quiet.

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, composed more than 2000 years ago, outline a path that is radically inward. A path not about performance, visibility, or personal branding, but about transcending the fluctuations of the mind.

In Patanjali’s world, yoga wasn’t a career. It wasn’t content. It wasn’t meant to be filmed, shared, or monetized. It was about renouncing the world, the senses, the distractions, the ego’s constant hunger for attention. It was about withdrawal, silence, and a kind of radical inwardness that very few modern practitioners can even imagine.

And yet, here we are, in a world where yoga has become a lifestyle, a profession, a visual language, and a global business. This doesn’t make it wrong or impure. It makes it different.

The truth is, the yoga most of us practice today is far from Patanjali’s vision. Even those who insist on the “essence” rarely live that renunciation in a literal sense.

We practice in studios, on beaches, in front of cameras. We document, post, brand, and teach. And for many of us, yoga is intertwined with work, community, and visibility.

It’s not the same path. But it is still a path.

To understand how we arrived here, we need to trace the journey of how yoga stepped out of the forest and onto the stage.

Yogananda and Vivekananda: the first global voices

The roots of yoga are quiet.

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, composed more than 2000 years ago, outline a path that is radically inward. A path not about performance, visibility, or personal branding, but about transcending the fluctuations of the mind.

In Patanjali’s world, yoga wasn’t a career. It wasn’t content. It wasn’t meant to be filmed, shared, or monetized. It was about renouncing the world, the senses, the distractions, the ego’s constant hunger for attention. It was about withdrawal, silence, and a kind of radical inwardness that very few modern practitioners can even imagine.

And yet, here we are, in a world where yoga has become a lifestyle, a profession, a visual language, and a global business. This doesn’t make it wrong or impure. It makes it different.

The truth is, the yoga most of us practice today is far from Patanjali’s vision. Even those who insist on the “essence” rarely live that renunciation in a literal sense.

We practice in studios, on beaches, in front of cameras. We document, post, brand, and teach. And for many of us, yoga is intertwined with work, community, and visibility.

It’s not the same path. But it is still a path.

To understand how we arrived here, we need to trace the journey of how yoga stepped out of the forest and onto the stage.

Krishnamacharya and the power of demonstration

While Yogananda was speaking in Los Angeles, another story was unfolding in Mysore.

In the 1930s, Tirumalai Krishnamacharya began teaching yoga at the Mysore Palace under the patronage of the Maharaja. He studied ancient texts, practiced intensely, and wove together elements of traditional Hatha yoga, Indian wrestling, and Western gymnastics into something dynamic, structured, and visually captivating.

Krishnamacharya did not invent the idea of bringing yoga onto a stage. In India, public demonstrations of dance, music, martial arts, and other embodied practices had long been part of the cultural fabric. These performances were not only entertainment but also a way of preserving traditions, sharing lineages, and transmitting cultural values.

What made Krishnamacharya’s contribution unique was that he brought yoga back into that public arena at a time when it had largely faded from view. Under colonial rule, yoga was often dismissed as backward or superstitious, and its public presence had diminished. Krishnamacharya used a familiar format - the demonstration - to reposition yoga as something vital, disciplined, and powerful.

He selected his most advanced students to perform intricate sequences and displays of strength, flexibility, and control. These were not quiet, private lessons. They were carefully crafted spectacles designed to inspire, impress, and legitimize yoga again in the eyes of the public.

A young Pattabhi Jois was in the audience during one of these demonstrations. What he saw that day changed his life forever. He became Krishnamacharya’s student, and eventually the Ashtanga method was born.

There is still black-and-white footage of Krishnamacharya from 1938 demonstrating advanced asanas with extraordinary control and grace. Silent film. Bare feet on the floor. His body moving with precision. It looks nothing like modern influencer content, but itiscontent. It was meant to be seen.

Krishnamacharya didn’t invent the stage.

He understood how to use it.

Iyengar. Light on image

Then came B.K.S. Iyengar, one of Krishnamacharya’s most famous students.

Iyengar was a visionary not only in his method but also in how he shared it. He worked with photographers, filmmakers, and publishers to document and distribute his teachings. His collaborations with Yehudi Menuhin, the world-renowned violinist, opened doors to international audiences.

His book Light on Yoga became an icon. Its clean black-and-white photographs became reference images for generations of practitioners. Iyengar understood what many teachers still resist today: that an image can be more than marketing. It can be a bridge.

Without those photographs, without that clear communication, Iyengar Yoga might have remained a local method. Instead, it became a global movement.

The celebrity era

In the 1980s and 90s, something shifted again.

Yoga entered pop culture.

Sting practiced Ashtanga. Madonna practiced Ashtanga. Christy Turlington, Gwyneth Paltrow, and other cultural icons brought yoga out of the yoga hall and into global media. Magazines, TV interviews, and documentaries made yoga visible in a way no sutra alone could have done.

Yes, this came with simplifications, distortions, and glossy aesthetics. But for millions of people, this was their first spark. The practice was no longer limited to a niche. It became part of the cultural conversation.

VHS, DVDs and the slow algorithm

Before Instagram, before algorithms and Reels, there were VHS tapes and DVDs.

Yoga teachers recorded their classes. Students practiced in living rooms, bedrooms, and basements, often thousands of kilometers away. Those tapes traveled slowly, hand to hand, shop to shop, sometimes bootlegged. But they traveled.

That was marketing. Just analog.

I still remember my first Ashtanga practice with an illegally burned David Swenson DVD. A friend passed it to me and said, “You should try this.” That piece of plastic changed everything for me. It was my first entry into a practice that would shape the rest of my life.

For many people of my generation, yoga didn’t start in a shala. It started on a fuzzy screen.

The digital stage

Temples. Theaters. Microphones. Photographs. VHS tapes. And now, the feed.

Instagram and TikTok didn’t invent visibility. They just made it immediate, accessible, and amplified. A global stage that fits in your hand.

This acceleration, of course, comes with its own shadows. Trends, performance pressure, algorithmic visibility over depth. But the principle hasn’t changed. Yoga has always had its storytellers and ambassadors. Every generation finds its own way to spread the practice.

The problem isn’t visibility. The problem is when visibility becomes a mask that covers the essence.

Visibility vs Performance

Visibility is not the enemy.

Losing yourself in performance is.

Patanjali’s yoga was a path of renunciation. Modern yoga lives in a world of images and voices. That’s the paradox. And also the opportunity.

We can choose to reject visibility altogether. Or we can learn to inhabit it without letting it swallow us. To share without selling out. To step onto the modern stage with intention.

This is what separates the scroll from the transmission.

The problem isn’t visibility. The problem is when visibility becomes a mask that covers the essence.

Reclaiming the stage

Vivekananda had a stage.

Yogananda had a microphone.

Krishnamacharya had his demonstrations.

Iyengar had photographs.

Sting had celebrity.

Swenson had DVDs.

We have reels.

Different tools. Same impulse.

This is not about becoming influencers. It’s about reclaiming authorship. About choosing how the story of yoga is told, instead of letting the loudest or most superficial voices shape it for us.

The problem isn’t visibility. The problem is when visibility becomes a mask that covers the essence.

My story, our story.

When I picked up that burned DVD years ago, I had no idea where it would lead.

No algorithm. No audience. No strategy. Just a spark.

That spark grew into a practice.

The practice grew into a journey.

The journey turned into a voice.

I’ve spent years behind the lens, capturing others’ practices, and now also stepping in front of it. What I’ve learned is simple: if good teachers stay silent, the story gets told by someone else.

And often, it’s a thinner story. A louder one. But not necessarily a wiser one.

The problem isn’t visibility. The problem is when visibility becomes a mask that covers the essence.

The stage is here

We don’t live in the forest anymore.

We live in the flow of information.

Before Instagram, there was a stage.

And after Instagram, there will be another.

The shape of the stage will keep changing. But the question remains the same:

Who will tell the story of yoga?

I’ve spent years behind the lens, capturing others’ practices, and now also stepping in front of it. What I’ve learned is simple: if good teachers stay silent, the story gets told by someone else.

And often, it’s a thinner story. A louder one. But not necessarily a wiser one.

The problem isn’t visibility. The problem is when visibility becomes a mask that covers the essence.

The stage is here

To every teacher who hesitates to be seen because it feels impure, commercial, or shallow, I see you. I understand that fear. But being visible doesn’t mean betraying the practice. It means standing for it.

The world doesn’t need more perfect performances.

It needs more honest presences.

If you don’t tell your story, someone else with less depth will. And they already are.

Step onto the stage, your way.

With integrity. With clarity. With heart.

If this resonates:

Share it with a teacher who inspires you.

Reflect on your own entry point into this practice.

Remember that the way we share yoga shapes the way the world meets it.